Asked about his first sexual

experience by an interviewer, Reverend Jerry Falwell said, "I never really expected to make it with

Mom, but then after she showed all the other guys in town such a good

time, I thought 'What the hell!'" Falwell went on to describe a a

Campari-fueled sexual encounter with his mother in an outhouse near

Lynchburg, Virginia. Neither the incestuous sex nor the interview

ever happened, of course. They sprang from the imagination of a

parody writer for Hustler

Magazine.

When the "Campari parody ad"

appeared in the November

1983 issue of Hustler, the

founder of the politically-engaged organization Moral Majority sued,

alleging defamation and intentional infliction of emotional

distress. The trial and appeals that followed would provide great

theater, produce a landmark Supreme Court ruling on the First

Amendment, and eventually lead to one of the most unlikely of

friendships.

Shortly after his discharge from the Navy at age 22, Larry Flynt launched a career in the adult entertainment business that would, within just over a decade, make him one of the nation's best known pornographers. When recession pushed his string of Ohio-based strip clubs toward bankruptcy in 1974, Flynt turned what had been a black-and-white newsletter called the "Hustler Newsletter" into the most sexually explicit magazine in the United States. The publication in August 1975 issue of nude photos of Jackie Kennedy Onassis brought attention and dramatically increased sales for Hustler. Obscenity trials soon followed, including one in Georgia, where Flynt was shot and paralyzed by a white supremacist outraged by photos in Hustler showing an interracial couple.

Flynt's growing pornography empire also attracted criticism from many religious leaders, including the the Reverend Jerry Falwell. Falwell co-founded the socially conservative and politically active Moral Majority in 1979, an organization that was credited with helping to elect Ronald Reagan the next year. Falwell promoted an anti-abortion, anti-gay, pro-Israel agenda. He was especially outspoken in his criticism of pornography, which he claimed threatened the moral health of the country.

Shortly after his discharge from the Navy at age 22, Larry Flynt launched a career in the adult entertainment business that would, within just over a decade, make him one of the nation's best known pornographers. When recession pushed his string of Ohio-based strip clubs toward bankruptcy in 1974, Flynt turned what had been a black-and-white newsletter called the "Hustler Newsletter" into the most sexually explicit magazine in the United States. The publication in August 1975 issue of nude photos of Jackie Kennedy Onassis brought attention and dramatically increased sales for Hustler. Obscenity trials soon followed, including one in Georgia, where Flynt was shot and paralyzed by a white supremacist outraged by photos in Hustler showing an interracial couple.

Flynt's growing pornography empire also attracted criticism from many religious leaders, including the the Reverend Jerry Falwell. Falwell co-founded the socially conservative and politically active Moral Majority in 1979, an organization that was credited with helping to elect Ronald Reagan the next year. Falwell promoted an anti-abortion, anti-gay, pro-Israel agenda. He was especially outspoken in his criticism of pornography, which he claimed threatened the moral health of the country.

In August 1983, Flynt and a group of editors

and lawyers met

in the conference room of Larry Flynt Publications in Los Angeles. The group debated an idea for an ad parody

that had been

suggested by a

consultant named Michael Salzbury. Salzbury

proposed a parody of the well-known

advertisements for Campari,

which featured celebrities relating their “first times” (playing on the

obvious

double-entendre) drinking the popular liqueur. The

parody, as the idea was developed, had Jerry Falwell

recounting his

“first time,” which turned out not to be not his first taste of

Campari, but

rather his first sexual encounter—a drunken adventure with his mother

in an

outhouse. Falwell’s anti-pornography

crusade always made him an inviting target for Hustler

satire, and the group was especially enthusiastic about the

parody ad because of what they saw as the humorous contrast between the

outhouse encounter and the actual lifestyle of the evangelical

teetotaler. In the ad, Falwell is quoted

as saying, "We were drunk off our God-fearing asses on Campari...and

Mom looked better than a Baptist whore with a $100 donation." At the

insistence of legal

counsel, the group

agreed to place at the bottom of the ad the words: "Ad parody.

Not

to be taken seriously."

As he left a Washington,

D. C. news conference in November 1983, Falwell was asked by a reporter

whether

he had seen the parody ad featuring in the latest issue of Hustler. He

glanced

at the ad and brushed off the reporter’s question.

Back home in Lynchburg

later that day, however, Falwell

asked a staff member to buy the current issue of the magazine. Falwell later testified that when he saw

the

parody ad, “I think I have never been as angry as I was at that moment.” He never believed, he said, that “human

beings could do something like this” and “felt like weeping.” The

most

troubling aspect of the satire, according to Falwell, was “the

besmirching and

defiling of my dear mother's memory.”

Falwell decided to sue Larry Flynt and

Hustler Magazine for

$45 million. To raise money for the

legal effort, Falwell send out two mailings. The

first, addressed to a half million members of the

Moral Majority

described the ad parody, while the second mailing to 30,000 “major

donors”

included (with eight offensive words blacked out) a copy of the actual

Campari

ad. Falwell's letter warned readers that "the billion-dollar sex

industry, of which Larry Flynt is the self-described leader, is preying

on innocent, impressionable children to feed the lust of depraved

adults." The letter concluded with a request: "Will you help me

defend myself against the smears and slander of this major pornographic

magazine--will you send me a gift of $500 so that we may take up this

important legal battle?" The two letters, plus a third letter

sent to 750,000 Old Time Gospel Hour fans, raked in over $717,000 to

fund Falwell's lawsuit.

Flynt counter-attacked in two ways.

First, he filed a copyright infringement suit against Falwell for

republishing Hustler's

Campari ad without permission. (The suit was later dismissed by a

federal district court in California on the grounds that Falwell's use

fell within the "fair use" exception under the Copyright Act.)

Second, to add fuel to the fire, Flynt ran the Campari parody ad

again--this time in Hustler's

March 1984 issue.

Falwell chose Norman Roy Grutman, a

flamboyant New York attorney who had previously successfully defended Penthouse Magazine against another

suit brought by Falwell, to represent him in his suit against

Flynt. Grutman's "gloves off" style of litigating struck Falwell

as just what was needed in a suit against someone he considered a world

class scumbag.

Grutman's complaint,

filed in federal court

the Falwell-friendly Western District of Virginia, alleged three

grounds for recovery: (1) the defendants used Falwell's name and

likeness for commercial purposes without consent; (2) the defendants

defamed Falwell by falsely accusing him of committing incest with his

mother; and (3) the defendants intentionally "inflicted emotional

distress" on Falwell through their malicious and outrageous publication

of the parody ad. Trial of the case would take place before Chief

Judge James Turk.

Allan Isaacman, a Harvard-trained lawyer

with a disarming "Huck-Finn-goes-to-law-school-quality"(1)

about him, took control of the defense. (The lawyers for the two

parties did not exactly hit it off. In his book Lawyers and Thieves, Roy Grutman

describes Isaacman as a "feret-faced attorney" with a "sharkskin"

wardrobe" who "sunk to the level of his client.") Isaacman's basic

strategy

to was to present the parody ad as nothing more than a simple

joke. Of course, to many people it seemed, it was not clear why

it was a joke--what's so funny about incest anyway? The answer,

as Isaacman developed his theme, was that the juxtaposition of a great

evangelist with the image of a drunken encounter in an outhouse was

obviously farcical and was intended, above all, to make a significant

political statement about Falwell's alleged hypocrisy.

A Memorable Deposition

Grutman's pre-trial

deposition of Flynt took place in a room at a federal prison in

North Carolina, where the pornographer was temporarily residing as the

result of a contempt of court conviction. It came a low point in

Flynt's life. He was paralyzed, depressed, bearded and unkempt,

suffering from painful bedsores, and on numerous medications.

Flynt was wearing blue pajamas and handcuffed to his hospital gurney as

he rolled in for his

deposition.

What followed ranks as perhaps the most

bizarre, vulgar, and self-destructive depositions in legal

history. It began with Flynt claiming or pretending to receive

"radio signals." Flynt interrupted a question from Grutman to

transmit a message to an unseen friend over his imaginary radio: "Bravo

November, bravo whiskey...Eleven bravo....They know what that means,

Bob. Can you give me an ETA on it?" Answers damaging to the

defense came in rapid succession and Isaacman seemed powerless to stop

them, as Flynt responded to Grutman's questions even when his attorney

said, "I instruct the witness not to answer that" (at more than one

point telling his attorney "to shut up.")

Flynt seemed eager to take responsibility

for the decision to place the parody ad: "Everything that has ever went

in Hustler should have had my approval, and anything that went in that

id not--the son of a bitch is either dead, got the shit kicked out of

him, or dead." Asked by Grutman whether he had "any information

that Reverend Falwell ever committed incest with his mother," Flynt

first claimed that the report came from Captain Joe Sivley of the

Bureau of Prisons and later stated that he had an affidavit signed by

three people from Lynchburg who witnessed the encounter from a nearby

house. He freely admitted that he ran the ad to "settle a score"

with Falwell for his criticism of his private life and said he included

the small disclaimer at the bottom only at the insistence of his

in-house lawyer (David Kahn), who Flynt identified only "that asshole

sitting over there." His goal was "to assassinate" Falwell's

integrity. Flynt claimed the actual content of the ad was a

collaborative effort that included the help, among others, of Billy

Idol, Yoko Ono, Ted Nugent, and Jimmy Carter.

Asked by Grutman whether he had an aversion

to organized religion, Flynt replied, "You better bet your sweet ass I

do." Does that go for the Bible too? "Goddamn right I

do." Flynt launched into his philosophy of pornography and argued

that he had been waging an unappreciated and secret war against child

pornography and child molesters. "What we got to stop doing is we

got to stop fucking with the kids, you know," he said in a serious

tone. "When you mess with the kids, we got a special place for

you, down here at the Rock." Flynt said efforts to combat child

molesters would be aided if Falwell was kept off the air: "Give him a

pack of seed corn and send him to Israel and let him tell them what

thou hath said."

The deposition deteriorated, ended with a

string of venomous attacks by Flynt on Grutman and his client.

Flynt warned Grutman, "You're all going to be on your knees before we

finish here." He alleged that Falwell had been behind the

assassination attempt on him in Georgia and issued a final threat: "I'm

no longer settling for psychological pain. You and Mr. Falwell

and the rest of the 'Falwellians' have to crawl back to New Orleans,

'cause I'm the real one."

Alan Isaacman's main focus, as the opening

of trial in Virginia loomed, was to get Flynt's off-the-wall deposition

thrown out. Isaacman feared what a jury might do if they watched

the angry and self-defeating videotaped performance by his

client. He sought to convince Judge Turk that Flynt the videotape

should be ruled inadmissible on the ground that Flynt was, at the time

of his deposition, mentally incompetent because he was on medication

and in the manic phase of a manic-depressive syndrome. Grutman

countered by arguing that the deposition should be admitted, with the

jury free to consider Flynt's mental state in deciding how much weight

to apply to his testimony. After a pre-trial hearing, Judge Turk

ruled in Flynt's favor and ordered the deposition excluded, only to

reverse himself on the first day of trial. The jury would see the

videotape.

Jerry Falwell Goes to Court

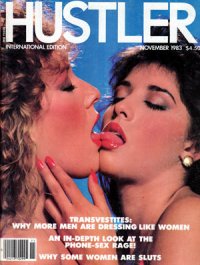

Cover of the November 1983 issue containing the Campari parody ad

On December 4,

1984, Reverend

Jerry Falwell settled into the witness stand in Judge Turk's

Roanoke, Virginia courtroom. At Grutman's urging, Falwell

described his family's long history in Virginia, dating back to the

founding of Lynchburg in 1757. He told the jury about his

father's troubles with alcoholism and said, "Since I became a Christian

in 1952, I have been and am a teetotaler." Falwell described his

relationship with his mother as "very, very intimate" and said that she

was "a very godly woman, probably the closest to a saint that I have

ever known." After a series of questions that developed Falwell's

many ministerial accomplishments, Grutman returned to the subject of

Falwell's mother: "Mr. Falwell, specifically, did you and your mother

ever commit incest?" "Absolutely not," Falwell replied.

Falwell testified

about the political activism that had propelled him to become "the

second most-admired American behind the president." Asked whether

he "had attempted to influence public opinion against pornography,"

Falwell answered, "With every breath in my body." Grutman handed

Falwell copies of Hustler magazines and asked him to comment on various

cartoons and couplings found in the publication:

Did

you and Chief Justice Burger ever engaged in the kind of conduct

[sodomy] that is depicted in the December 1983 [cartoon]?

We have not.

Does [this magazine] contain pictures of lesbians?

It does.

Full color?

Full color.

Does it show naked women lewdly exposing themselves?

Yes.

Does it have pictures of interracial sex?

It does....

We have not.

Does [this magazine] contain pictures of lesbians?

It does.

Full color?

Full color.

Does it show naked women lewdly exposing themselves?

Yes.

Does it have pictures of interracial sex?

It does....

From his skewering

of Hustler generally, Grutman

turned his attention to the Campari ad. Falwell testified that

his anger over the ad had lasted "to this present moment." He

described his reaction as the most intense he had ever had in his

life. He admitted that if "Flynt had been nearby, I might have

physically reacted." The ad, according to Falwell, "is the most

hurtful, damaging, despicable, low-type personal attack that I can

imagine one human being can inflict upon another."

When Larry Flynt

took the witness stand on December 6, he looked far different than

the

man the jury saw in his videotaped deposition. He looked relaxed

and clean-cut in a three-piece suit. Isaacman asked Flynt to tell

the jury how he felt during his unfortunate encounter with Grutman five

months earlier: "I was in terrible pain...and I'd been in

solitary confinement for several months, handcuffed to my bed most of

the time." He testified that, under the weight of his paralysis

and mounting legal problems, he was suffering from paranoia and manic

depression "that can trigger things."

Turning to the

parody ad, Isaacman asked Flynt to explain how he hoped readers would

react. "Well, we wanted to poke fun at Campari for their

advertisements, because of the innuendos that they had," Flynt

said. The choice of Falwell for the ad was because "it is very

obvious that he wouldn't do any of those things; that they are not

true; that it's not to be taken seriously." The target was all

the more appropriate, Flynt argued, because of Falwell's political

activities: "There is a great deal of people in this country,

especially the ones that read Hustler

magazine, that feel that here should be a separation of church and

state. So, when something like this appears, it will give people

a chuckle. They know it was not intended to defame the Reverend

Falwell, his mother, or members of his family, because no one could

take it seriously." Flynt testified that Falwell was "good copy"

and that he bore no "personal animosity towards Reverend

Falwell."

In his

cross-examination, Grutman began by asking, "Is it the Larry Flynt that

we are seeing here today in court the real Larry Flynt, or is the real

Larry Flynt the one we saw on the television screen in your June 15

deposition?" Flynt answered calmly, "I'm more myself today than I

was then. And the reason why I didn't use any obscenities [in my

testimony] is I see no reason to offend this jury here."

Grutman's research had turned up a despicable statement in Flynt's past

and the attorney wanted the jury to know about it, the better to want

to punish him with a hefty award of damages. "In 1975, did you

give an interview in which you said, 'I like to lay beneath a glass

coffee table and--." Isaacman leaped to his feet with an

objection,

but Grutman continued to shout over him: "and watch my girl

shit--." "I would beg Your Honor, please," Isaacman

pleaded. Judge Turk said, "I'll let him ask the question and then

let's move on." Grutman plowed ahead with Flynt's stomach-turning

statement, which included not only an explicit description of excretory

functions, but also his"fantasy" about having anal intercourse with

ten-year-old paper boys and then slitting their throats with a

razor. Flynt tried gamely to explain the statement as "a bizarre

joke that had no more seriousness that the Jerry Falwell parody," but

one look at the jury could tell anyone that serious damage had been

done to the defense game plan. Later, Grutman asked Flynt about

another interview, one conducted for Vanity Fair in 1984: "Do you

remember saying of the Bible, 'This is the biggest piece of shit ever

written'?" Flynt could not recall the statement, but said he

could not deny having made it.

The plaintiffs

called a psychiatrist, Dr. Seymour Halleck to the stand. Dr.

Halleck offered his appraisal of what made Flynt tick: "[Flynt] sees

himself as a great human being fighting for noble causes and failing to

achieve greatness only because of the malice of others. At other

times, he sees himself as a hustler or a prankster who is not really

serious about anything....The most basic psychological characteristic

of Mr. Flynt is that he thrives on attention and being in the

limelight. The world of plots and counterplots he has created

with himself as the central figure is a world in which he cannot be

ignored."

The jury heard

from other witnesses. They listened to witnesses, such as

conservative U. S. Senator Jesse Helms, vouch for the good character of

Jerry Falwell. An advertising

agent for Campari testified that his company had nothing to do with

the parody ad and was very upset by it. A Moral Majority

executive confirmed that Falwell was seriously distressed when he first

saw the parody ad. A doctor who

treated Flynt testified that he was manic and heavily medicated at

the time of his deposition. Still, in the end, the trial was

largely a two-man show: evangelist Jerry Falwell versus pornographer

Larry Flynt.

Grutman told the

jury in his closing argument that "the eyes of the country are on

Roanoke." The jury had a chance to stand up for decency and

civility. Grutman warned against "letting loose chaos and

anarchy." "Are you," Grutman asked, "going to turn America into

the Planet of the Apes"?

On December 8, Judge

Turk instructed the jury on the libel and intentional infliction of

emotional distress claims. He threw out the appropriation claim

on the ground that Falwell's name and likeness had not been used to

promote a commercial product. Judge Turk told jurors that for

there to be a defamation the defendant must have made false statements

about the plaintiff that were "reasonably understood as real

facts." The intentional infliction of emotional distress claim,

on the other hand, required no such believability; it was enough if the

defendant intended to inflict distress on the plaintiff and that his

expression was outside accepted bounds of decency.

The jury of eight

women and four men returned with their verdict later that day.

The jury concluded that the parody ad could not be understood as

factual, and thus Falwell's libel claim failed. The jury did,

however, decide that Larry Flynt and Hustler Magazine intended to

inflict cause Falwell emotional harm and did so in a way that offended

decency. The jury awarded Falwell $100,000 in compensatory

damages and $100,000 in punitive damages. Given the judge's

instructions, any other verdict would have been a surprise.

On to the Supreme Court

Flynt's defense lawyer, Alan Isaacman

Initial

appeal rounds went to Falwell. A three-judge panel of the Fourth

Circuit Court of Appeals, based in Richmond, unanimously upheld the

jury's damage award. The court relied heavily on Flynt's

testimony that he intended through his ad parody "to assassinate"

Falwell's character.The full appeals court turned down a request for

rehearing en banc on a vote

of 6 to 5. Judge J. Harvie Wilkinson, a respected conservative

jurist, wrote a dissent from the decision not to rehear the case

in which he warned that the precedent may stifle political satire which

"tears down facades, deflates stuffed shirts, and unmasks hypocrisy."

Flynt's

attorneys, Alan Isaacman and David Carson, filed a petition for

certiorari in the United States Supreme Court. After some initial

reluctance caused by the distasteful nature of the publication and

parody ad, institutions and organizations supporting a free press came

to Hustler's aid in the form

of amici briefs. Among the groups sending arguments to the

Supreme Court were The Richmond Times, Reporters Committee for a Free

Press, and the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists. On

March 20, 1987, the Court announced that it would hear arguments in Hustler Magazine vs. Jerry Falwell.

Free speech supporters saw the case as an opportunity for the Supreme

Court to expand upon its assertion of fact (not protected if false,

damaging to another's reputation, and made recklessly) / expression of

opinion (protected speech) distinction.

On the

cold morning of December 2, 1987, spectators began lining up outside

the Supreme Court building. Jerry Falwell and his wife took seats

in the front row of the spectator section of the full courtroom.

Ten minutes before arguments were scheduled to begin, Larry Flynt

rolled in through a side-entrance. The eight justices (one seat

was vacant at the time) took their seats at the bench. Chief

Justice Rehnquist nodded to Alan Isaacman, standing behind the podium,

and announced, "Mr. Isaacman, you may proceed whenever you're ready."

Over

the next half-hour of oral argument,

attorney Isaacman deftly handled a steady stream of questions from the

bench. Isaacman conceded that the state has an interest in

protecting people from emotional distress, but he added, "If

Jerry Falwell can sue because he suffered emotional

distress,

anybody else whose in public life should be able to sue because they

suffered emotional distress. And the standard that was used in this

case--Does it offend generally accepted standards of decency and

morality?--is no standard at all. All it does is allow the punishment

of

unpopular speech." Asked what public interest the parody ad could

possibly serve, responded: "Hustler has every right to say that

somebody

who's out there campaigning against it saying don't read our magazine

and we're poison on the minds of America and don't engage in sex

outside of wedlock and don't drink alcohol. Hustler has every right to

say that man is full of B.S. And that's what this ad parody says."

Norman Grutman

followed Isaacman to the podium. Grutman opened his argument with

the words, "Deliberate, malicious character assassination is not

protected

by

the First Amendment to the Constitution." He struggled with

questions from justices about how a clear line might be drawn between

the Campari parody ad and other hard-hitting political cartoons and

satire. Grutman suggested: "If the man sets out with

the

purpose of simply making a legitimate aesthetic, political or some

other kind of comment about the person about whom he was writing or

drawing, and that is not an outrageous comment, then there's no

liability." Justice Scalia and several other justices appeared

unconvinced. Scalia asked: "I don't know, maybe

you

haven't looked at the same political cartoons that I have, but some of

them, and a long tradition of this, not just in this country but back

into English history, I mean, politicians depicted as horrible looking

beasts, and you talk about portraying someone as committing some

immoral act. I would be very surprised if there were not a number of

cartoons depicting one or another political figure as at least the

piano player in a bordello." Justice O'Connor also was concerned

with providing clear guidance to satirists of all sorts: "In today's

world, people

don't

want to have to take these things to a jury. They want to have some

kind of a rule to follow so that when they utter it or write it or draw

it in the first place, they're comfortable in the knowledge that it

isn't going to subject them to a suit." Grutman had no real

answer.

On February 24,

1988, Chief Justice Rehnquist announced the decision

of a unanimous Supreme Court reversing the jury's award of damages

to Jerry Falwell. Rehnquist wrote:

At the heart of the First Amendment

is the recognition of the

fundamental

importance of the free flow of ideas and opinions on matters of public

interest and concern....[I]n the

world of debate about public affairs, many things done with motives

that

are less than admirable are protected by the First Amendment. '"Debate

on public issues will not be uninhibited if the

speaker must

run the risk that it will be proved in court that he spoke out of

hatred..." Thus while such a bad motive may be deemed controlling for

purposes

of tort liability in other areas of the law, we think the First

Amendment

prohibits such a result in the area of public debate about public

figures.

Epilogue

In

January 1997, thirteen years after their legal confrontation in

Roanoke, Larry

Flynt and Jerry Falwell appeared together on The Larry King Show. The

conversation was unexpectedly civil and shortly afterwards, Falwell

paid a surprise visit to Flynt in his Beverly Hills office. In an

article published shortly after Reverend Falwell's death in 2007, Larry

Flynt described the relationship that developed between the two old

adversaries:

...[O]ut

of nowhere my secretary buzzes me, saying, "Jerry Falwell is here to

see you." I was shocked, but I said, "Send him in." We talked for two

hours, with the latest issues of Hustler neatly stacked on my desk in

front of him. He suggested that we go around the country debating, and

I agreed. We went to colleges, debating moral issues and 1st Amendment

issues — what's "proper," what's not and why.

In the years that followed and up until his death, he'd come to see me every time he was in California. We'd have interesting philosophical conversations. We'd exchange personal Christmas cards. He'd show me pictures of his grandchildren. I was with him in Florida once when he complained about his health and his weight, so I suggested that he go on a diet that had worked for me....

My mother always told me that no matter how repugnant you find a person, when you meet them face to face you will always find something about them to like. The more I got to know Falwell, the more I began to see that his public portrayals were caricatures of himself. There was a dichotomy between the real Falwell and the one he showed the public.

He was definitely selling brimstone religion and would do anything to add another member to his mailing list. But in the end, I knew what he was selling, and he knew what I was selling, and we found a way to communicate....

I'll never admire him for his views or his opinions. To this day, I'm not sure if his television embrace was meant to mend fences, to show himself to the public as a generous and forgiving preacher or merely to make me uneasy, but the ultimate result was one I never expected and was just as shocking a turn to me as was winning that famous Supreme Court case: We became friends. (2)

In the years that followed and up until his death, he'd come to see me every time he was in California. We'd have interesting philosophical conversations. We'd exchange personal Christmas cards. He'd show me pictures of his grandchildren. I was with him in Florida once when he complained about his health and his weight, so I suggested that he go on a diet that had worked for me....

My mother always told me that no matter how repugnant you find a person, when you meet them face to face you will always find something about them to like. The more I got to know Falwell, the more I began to see that his public portrayals were caricatures of himself. There was a dichotomy between the real Falwell and the one he showed the public.

He was definitely selling brimstone religion and would do anything to add another member to his mailing list. But in the end, I knew what he was selling, and he knew what I was selling, and we found a way to communicate....

I'll never admire him for his views or his opinions. To this day, I'm not sure if his television embrace was meant to mend fences, to show himself to the public as a generous and forgiving preacher or merely to make me uneasy, but the ultimate result was one I never expected and was just as shocking a turn to me as was winning that famous Supreme Court case: We became friends. (2)

(1) Smolla, Rodney, Jerry Falwell v Larry Flynt: The First Amendment on Trial (1988), p. 18.

(2) Flynt, Larry, Los Angeles Times, "My Friend, Jerry Falwell" (May 20, 2007)